Pancreatic cancer research faces significant challenges, partly because traditional preclinical models often fall short in capturing the complexity of human disease biology. The KPC cell line was developed to provide a robust tool for studying tumour biology, testing therapeutic compounds, and driving new discoveries. In this feature, we spoke with the inventor of the KPC cell line, Prof. Jennifer Morton, at Cancer Research UK Scotland Institute, to explore how the cell line was developed and to gain insights into its growing impact on pancreatic cancer research.

The challenge of modelling pancreatic cancer

Pancreatic cancer remains one of the most lethal malignancies, ranking as the sixth leading cause of cancer-related deaths worldwide (1). Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) accounts for more than 90% of all pancreatic tumours and is characterised by a complex and dynamic tumour microenvironment (TME) that drives disease progression and treatment resistance.

Despite significant research efforts, many preclinical models still fall short of capturing the full complexity of human pancreatic cancer, particularly the TME and disease heterogeneity, which limits their translational value. Traditional 2D cell line models, for instance, often fail to replicate key features such as interactions with stromal or immune components, leading to data that may not accurately predict clinical outcomes and contributing to the high failure rate of novel therapies in clinical trials.

Prof. Jennifer Morton, Cancer Research UK Scotland Institute

PDAC is also a highly heterogeneous disease, most commonly driven by alterations in KRAS, TP53, CDKN2A, and SMAD4 (2). Yet, current preclinical models rarely reflect this genetic and molecular diversity – a critical gap when developing personalised therapies that match the complexity of the disease. To address these challenges, the KPC cell line was developed by Professor Jennifer Morton and her team at the Cancer Research UK (CRUK) Scotland Institute. Engineered with mutations in both KRAS and TP53, the KPC cell line closely mirrors the genetics and physiology of human PDAC.

It provides researchers with a clinically relevant preclinical tool for studying tumour biology, evaluating therapeutic efficacy and toxicity, and advancing novel approaches including targeted therapies and immunotherapies, such as checkpoint inhibitors.

Introducing the scientist behind the KPC cell line

Prof. Jennifer Morton first joined the CRUK Scotland Institute as a postdoctoral researcher, focusing on pancreatic cancer mouse modelling. Now a Group Leader, her team uses genetically engineered mouse models (GEMMs) to mimic the driver mutations and immunosuppressive TME that define human PDAC, building clinically relevant tools for testing novel therapies that target both tumour cells and the surrounding stroma.

Driven by limitations of existing models, Prof. Morton set out to create a more rapid, flexible and scalable system. Her goal was to develop a model that could accelerate research while preserving the biological complexity needed for translational studies – a mission closely aligned with Cancer Research UK’s broader commitment to enabling impactful research through innovative and collaborative science.

A model built from challenge

The KPC cell line was developed from a well-established GEMM of pancreatic cancer, designed to mimic the aggressive nature of human PDAC. By simultaneously activating mutant KrasG12D and Trp53R172H in the mouse pancreas, researchers created mice that spontaneously develop invasive, metastatic pancreatic tumours – a key step forward in modelling the disease more realistically (3).

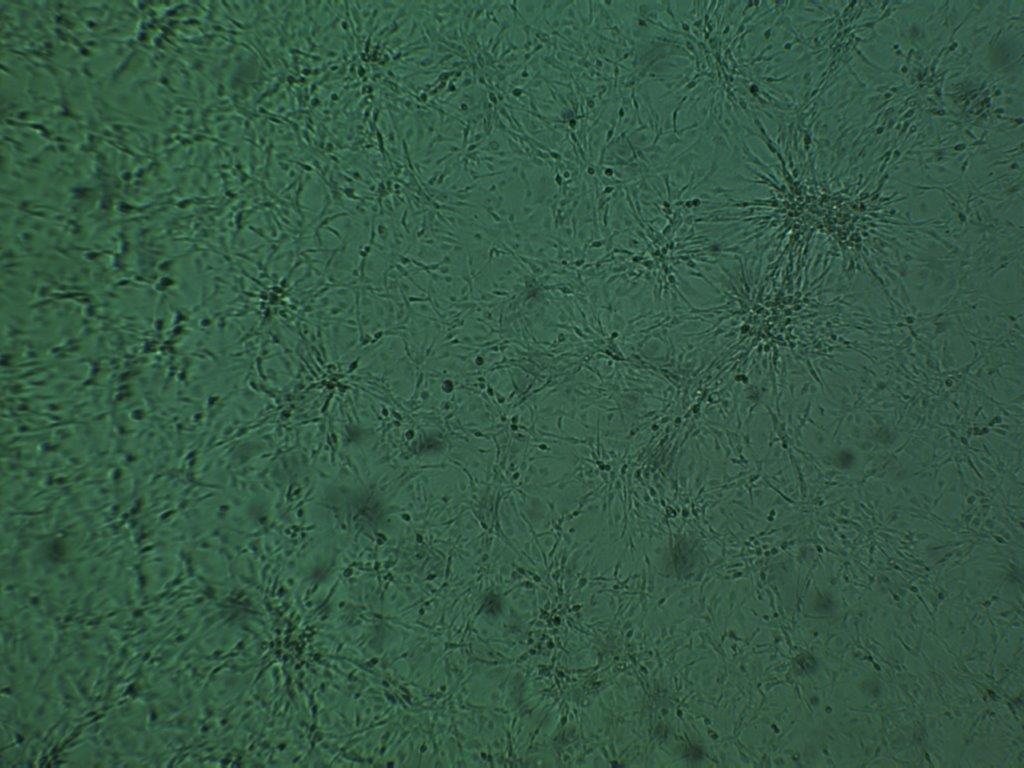

KPC cell line (C57/BL6 genetic background) cell sheet monolayer.

To make this model more accessible and enable flexible experimental modelling, Prof. Morton and her team established two transplantable KPC cell lines. These retain the key genetic drivers and tumour behaviour of the original model, but offer a faster, more scalable way to study disease progression and therapeutic response. One version was developed on a C57BL/6 background, making it especially useful for immuno-oncology and therapeutic response research.

While the pancreatic cancer cells themselves were relatively easy to culture, the process of generating the lines was not without challenges. The mouse models used are costly and time-intensive to maintain, which underscores the value of having a reliable, transplantable cell line that captures the complexity of the original model while being more accessible for diverse experimental settings.

This versatility has made the KPC cell line a unique resource in pancreatic cancer research. Whether studying tumour-stroma interactions, immune responses, or metastatic spread, it continues to enable impactful discoveries – something Prof. Morton has highlighted as a key contribution to the field.

The KPC cell line is important for researchers because it allows them to transplant pancreatic cancer cells into healthy mice with an intact immune system to study different aspects of pancreatic cancer development or progression. They can also use the models to test new treatments.

Prof. Jennifer Morton, Cancer Research UK Scotland Institute.

Sharing the KPC cell line

A major milestone in expanding the reach of the KPC cell line came through a collaboration between Prof. Morton and CancerTools, our not-for-profit research tool platform. This partnership made the cell line openly accessible to scientists worldwide, removing the logistical and time-consuming burden of distributing it directly from her lab and ensuring it reaches those who can use it most effectively.

We got a lot of requests from the research community for our cell lines. It was quite time-consuming and expensive for us to keep bulking them up and organising shipping to different labs. CancerTools has removed that burden from the people in my lab and makes our cell lines more visible to the community.

Prof. Jennifer Morton, Cancer Research UK Scotland Institute.

Traditionally, researchers have faced long email exchanges, material transfer agreements, and shipping delays when requesting cell lines from academic groups – hurdles that ultimately slow scientific progress. Through CancerTools, the KPC cell line can now be accessed quickly and reliably from a centralised, trusted source, allowing researchers to focus on discovery rather than paperwork.

CancerTools is aligned with Cancer Research UK’s broader mission to beat cancer through accelerated innovation and collaboration. Every cell line, antibody, patient-derived organoids or xenografts distributed through our platform generates funds that are returned to the originating inventor directly or via the originating institute, and reinvested into cancer research, creating a cycle that sustains and accelerates global scientific progress. Through this collaboration, CancerTools helps researchers produce comparable data across labs – making the science not only more robust, but also globally reproducible, amplifying the impact of each tool shared.

By making the KPC cell line available through CancerTools, Prof. Morton has helped build a culture of openness and collaboration. Her work now supports laboratories across the world, helping scientists push the boundaries of pancreatic cancer research.

From bench to publication

With the KPC cell line now widely accessible to labs worldwide, researchers are using it to explore how pancreatic tumours grow, spread, and resist treatment.

In Prof. Morton’s lab, the KPC cell line is being used to investigate how fibroblasts influence metastatic behaviour, particularly within the lungs and liver. By transplanting KPC cells intravenously or intrasplenically into mice with genetically modified fibroblasts, her team can study the TME in specific organs while isolating effects from the primary tumour. This approach allows researchers to uncover the role of a specific signalling pathway in the metastatic niche, offering new insights into how stromal cells shape cancer progression.

Mutant p53 enhances invasion in pancreatic cancer cells. An inverted-invasion assay comparing KPC cell lines shows that cells carrying the p53R172H mutation invade much more deeply into the matrix than cells with wild-type p53. Introducing mutant p53 into wild-type cells restores this highly invasive behaviour, demonstrating that mutant p53 actively drives tumour cell invasion. Image taken from Morton JP et al (4).

One of the most compelling applications of the KPC cell line has been in metastasis biology. Studies using tumour-derived KPC cells have shown that mutant p53 actively drives invasion and metastasis – a significant finding that has reshaped our understanding about PDAC progression (4). This insight has positioned the KPC cell line as a key tool for uncovering the molecular drivers of metastatic behaviour.

The KPC models have also helped uncover how immune signals reshape tumour .metabolism. By studying parental and IDO1-engineered KPC cell lines in immunocompetent mice, Newman and colleagues showed that interferon-γ drives strong IDO1 expression in KPC tumours, triggering tryptophan breakdown and supplying one-carbon units that fuel purine synthesis (5). Because these metabolic shifts became evident in vivo only when IDO1 is induced under immune-competent conditions, the study highlights how KPC cell lines uniquely capture tumour–immune metabolic interactions that are difficult to reproduce in vitro. This makes them a powerful tool for investigating metabolic and immunological vulnerabilities in PDAC.

Together, these applications highlight the versatility of the KPC cell line – a model that has helped uncover key drivers of metastasis and tumour metabolism in pancreatic cancer. It’s ability to recapitulate complex tumour biology in vivo makes it an ideal model for translational research, driving discoveries that are shaping the future of PDAC therapy.

Where do we go from here?

As pancreatic cancer research continues to evolve, so too does the need for more sophisticated and clinically relevant research models. With the emergence of KRAS inhibitors, researchers are hopeful that more patients will begin responding to targeted therapies. This progress is expected to drive a wave of studies focused on acquired resistance and the development of combination therapies, areas where models like the KPC cell line will remain essential.

The KPC cell line’s ability to replicate tumour progression and metastasis in immunocompetent mice makes it especially valuable for testing how tumours adapt under therapeutic pressure. As researchers seek to understand why some patients develop resistance to certain treatments, clinically relevant preclinical tools like the KPC cell line will help uncover the cellular dynamics behind resistance and inform strategies to overcome it.

Looking ahead, Prof. Morton sees opportunities to develop new models that address persistent gaps in the field. One area of interest is the study of dormant metastatic cells – those that remain in distant organs after the primary tumour is removed and later drive relapse. While these models have yet to be optimised, she believes it’s possible to transplant KPC cells, surgically resect the primary tumour, and track the emergence of metastases over time. Such a model would offer valuable insights into disease recurrence and long-term treatment plans.

A personal reflection and call to collaboration

For Prof. Morton, seeing the KPC cell line used by researchers around the world has been both professionally rewarding and personally meaningful.

Aside from saving my lab the time and money it takes to make the KPC cells available to the community, it’s been good to see a lot of different labs be able to make use of them for their research. Ultimately, the more scientists there are performing pancreatic cancer research, the more likely it is that new therapies will be developed for patients.

Prof. Jennifer Morton, Cancer Research UK Scotland Institute

Knowing that the KPC cell line is driving progress in pancreatic cancer research is a powerful reminder of what’s possible when science is shared – openly, collaboratively, and with purpose.

Explore the KPC cell line and be part of a global effort to accelerate breakthroughs in pancreatic cancer.

References

- Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, Laversanne M, Colombet M, Mery L, Piñeros M, Znaor A, Soerjomataram I, Bray F (2024). Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today. Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer. Available from: https://gco.iarc.who.int/today.

- Wang S, Zheng Y, Yang F, Zhu L, Zhu XQ, Wang ZF, et al. The molecular biology of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: translational challenges and clinical perspectives. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. 2021 Jul 5;6(1).

- Hingorani SR, Wang L, Multani AS, Combs C, Deramaudt TB, Hruban RH, et al. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005 May 1;7(5):469–83.

- Morton JP, Timpson P, Karim SA, Ridgway RA, Athineos D, Doyle B, et al. Mutant p53 drives metastasis and overcomes growth arrest/senescence in pancreatic cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009 Dec 15;107(1):246–51.

- Newman AC, Falcone M, Uribe AH, Zhang T, Athineos D, Pietzke M, et al. Immune-regulated IDO1-dependent tryptophan metabolism is source of one-carbon units for pancreatic cancer and stellate cells. Molecular Cell. 2021 Apr 7;81(11):2290-2302.